After decades of obscurity and neglect, the gut has become a subject of intense interest not only for scientists and physicians, but also for the public.

Almost overnight, gut health has become a popular topic at dinner conversations, in the media and of New York Times bestsellers, and venture capital funds have poured millions into startup companies aimed at improving gut health and treating gut-brain disorders.

As a doctor who has worked in the area of brain-gut interactions for the past thirty years, I find this new attention surprising, as the unique status of the gut—by which I mean the stomach, small intestine and large intestine—has long been known to a small community of researchers. The gut is home to the largest part of our immune system, many of our hormones, 95 percent of serotonin (a chemical that regulates sleep, appetite, pain sensitivity and mood), and a specialized gut-based nervous system that can regulate gut function more or less independently of our brain. In addition, the gut is an important interface with our environment, with a surface area of about 450 square feet—significantly larger than that of our skin.

A major reason for this explosion of interest was the discovery, about 15 years ago, of the gut microbiome—the hundreds of trillions of microorganisms that live inside our gut and produce thousands of signaling molecules (metabolites) from the food we eat. Using these metabolites, gut microorganisms communicate with each other, the gut itself, the immune system, the liver, and even the brain. The microbiome is the invisible link between the world around us—including the farms that produce our food—and our health.

As we understand more about the intricate interactions of these microorganisms and how they affect us, we’re adopting a radical new view of human health. We’re beginning to treat patients within the context of these microbial ecosystems—not only those inside the body, but also in the environment.

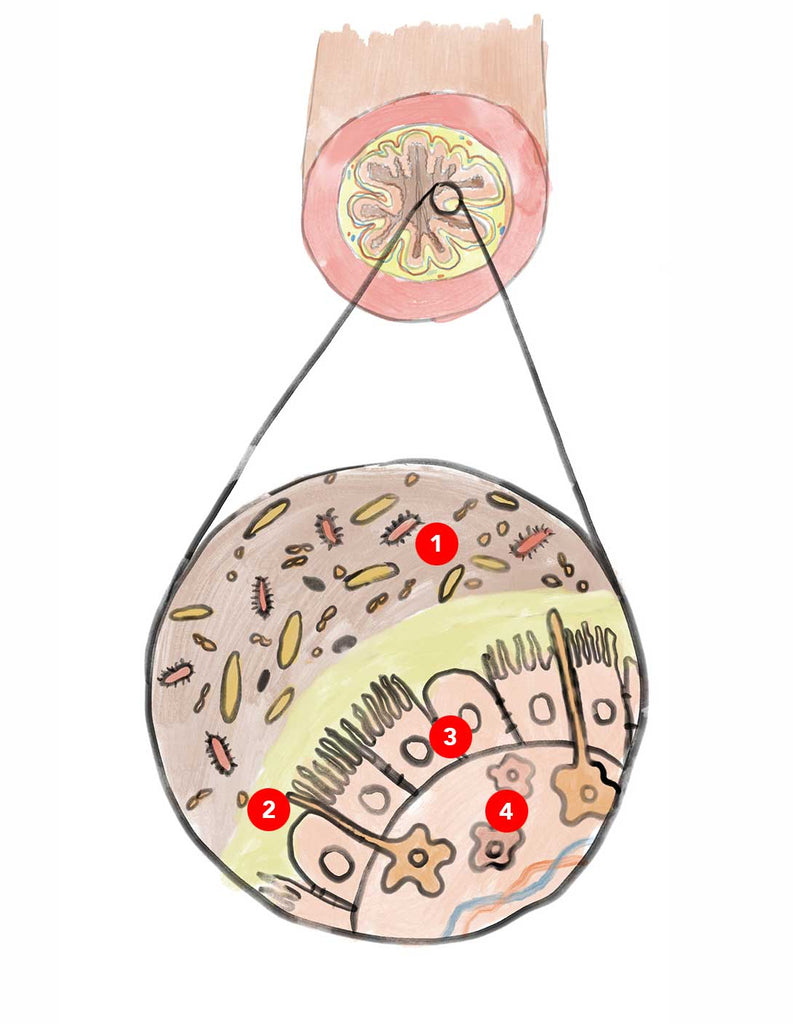

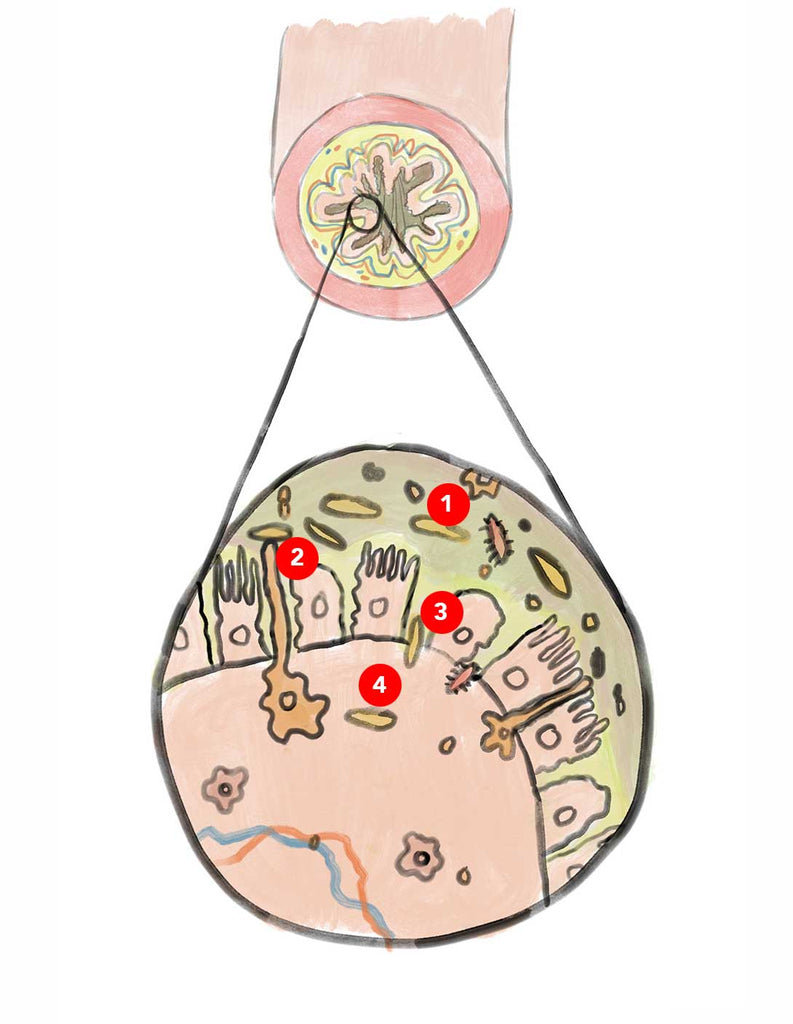

A Gut in Good Shape

A healthy gut is characterized by a tight barrier between the inside, where microbes break down your food, and the gut-associated immune system, which lies just beyond—and contains about 40 percent of the immune cells in our body. The barrier prevents direct contact between gut microbes and the immune system, thereby staving off full-blown immune activation. Even low-grade immune activation—so-called metabolic toxemia—has been implicated in the development of many chronic diseases, including metabolic syndrome, chronic fatigue, depression and degenerative brain disorders. A healthy gut also has a smoothly operating gut-based nervous system, which regulates peristalsis and the absorption and secretion of fluids.

All this depends in no small part on the health of the gut microbial ecosystem. Gut microbes communicate with each other and with other cells in their immediate vicinity, including immune cells, mucus-and hormone-producing cells, and nerve cells regulating gut function. It is the normal interaction between all these players in the gut ecosystem that determines not only gut health, but also our overall health. In other words, when our microbes are in top shape, our gut works well too.

As in any ecosystem, the health of the microbiome is determined by the diversity and abundance of its species. The greater the diversity, the more resilient it is and the more resistant to disease. A small group of gut microbes are considered keystone species, like the American bison is to the Great Plains or the wolves to Yellowstone; they are especially critical to the stability of their ecosystem. Many studies support the concept that a highly diverse gut microbiome with intact keystone species is associated with optimal gut health, and with a lower risk for such chronic diseases as type 2 diabetes, obesity, cognitive decline, Parkinson’s disease and depression.

Diversity in Decline

Likewise, resilience and disease resistance declines as diversity dwindles, ultimately reaching a tipping point, so that even minor perturbations can lead to catastrophic consequences. Many ecosystems around the world, including rainforests and coral reefs, are headed towards or have already reached such a point. Currently 25 percent of land animals and plants, 30 percent of birds and 33 percent of fish are threatened by extinction.

This dramatic loss has an invisible parallel in the microbial world, both in the soil and in our gut. Long-term continuous cropping and overuse of chemical fertilizers has dramatically degraded about 40 percent of the world’s agricultural soils, with a significant decline in soil biodiversity. Similarly, our urban North American gut microbiomes are 40 percent less diverse than the microbiomes of some hunter-gatherer societies on the Orinoco River in the Amazonian rainforest, or in the Rift Valley in East Africa—environments that remain relatively untouched by industrialization. These changes are apparent even in infants, ominously suggesting that an unhealthy diet can be transmitted from mother to child.

Considering that we have approximately 100 trillion microorganisms and 1000 species living in our gut, it’s easy to conclude that losing a few thousand may not make a big difference. However, scientists like Dr. Martin Blaser, director of the Human Biome Program at New York University, and many others have warned that if the microbial life inside us continues to plummet, health catastrophes may be on the horizon: pandemic gastrointestinal infections; a continued increase in autoimmune diseases like asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease; a possible rise in autism spectrum disorders; and a persisting epidemic of obesity and metabolic diseases.

Luckily, there is an alternative, and it doesn’t require much to implement.

The Optimal Diet

As Living Beings on this earth, we need the same dietary guidelines for our personal health as for the health of the planet, a perspective encouraged by the international, interdisciplinary One Health movement at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). The One Health idea, propagated by the international EAT Lancet Commission and slowly gaining traction among nutritionists, posits that optimal human health is directly related to the health of the soil and the environment, and that this interconnectedness is mediated by the most successful life-form on our planet: the microbes. If we change our food-raising practices to encourage diversity, we have a chance to improve not only the well-being of our own microbiomes, but also those of our soil and oceans.

How to Feed Your Microbiome

So how to put One Health into practice? The answer is relatively simple: Feed your microbiome what it needs to thrive. What’s good for your gut microbes is good for your overall health, and drives choices that benefit soil health too.

Microbes like a largely plant-based diet, with small amounts of pasture-raised organic meat and poultry and, if available, wild game. Choose a wide range of in-season plants—including vegetables, fruits, berries, spices and roots—to feed your microbiome a variety of different fibers, each of which is processed by a different species of microbe. This prompts the gut microbiome to become more diverse in order to handle the different fiber types, which it turns into health-promoting molecules.

Eat plants with large amounts of their own medicine, the polyphenols—large molecules that protect them against diseases and pests. Polyphenol levels are highest in certain berries (including blueberries, blackberries, and Nordic types like lingonberries and sea buckthorn), nuts, coffee, tea, olive oil, beans, red grapes, red wine and spices. While many of these molecules are too large to be absorbed by our small intestine, our gut microbes feed on them and break them down into smaller, absorbable health-promoting ones. Meanwhile, polyphenols seem to have a beneficial effect on gut microbial composition, suppressing pathogens and encouraging the growth of microbes that are good for us.

Choose seafood and meat rich in poly-and monounsaturated fatty acids and a high ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids. Several clinical studies have shown that eating these foods has a beneficial effect on the diversity and composition of the gut. Other studies indicate that these fats have a range of health benefits, including reducing inflammation and symptoms of depression and improving heart health. Wild salmon, sardines, mackerel, mussels, free-range and grass-fed chickens and cows, bison and wild game are all good sources; conventionally farmed animals have much lower levels. Plant-based oils from avocados, olives, walnuts and flax and chia seeds have these beneficial fats too.

Avoid processed carbohydrates and keep sugars to a minimum. White bread, white rice, and pasta—any food stripped of its natural fibers—and sugars are calorie-dense foods without many other nutrients and are rapidly absorbed in the first part of the small intestine. This rapid absorption results in elevated blood sugar levels and insulin spikes. It also starves our gut microbes—the great majority of which live in the lower part of the small intestine and in the large intestine.

Regularly eat foods with known anti-inflammatory properties, such as turmeric, ginseng and ginger, to minimize low-grade immune activation in the gut.

Regularly consume fermented foods, like yogurt, miso, and sauerkraut (choose brands that are naturally fermented with live bacteria, rather than quick-pickled types that get their zing from vinegar). All these foods contain benign microbes that have been associated with various health benefits, although the link hasn’t been definitively proven for most of these foods in controlled studies.

Lastly, try time-restricted eating. Studies have demonstrated that if you keep your gut completely empty for at least 10 hours a day, significant changes occur in your gut microbiome. This includes a reduction in the microbes’ interactions with the gut’s immune system, which lowers chronic immune activation.

Why Sourcing Matters

How your food is produced and harvested impacts your health, the nutrient value of the food, the welfare of animals and the environment.

Organic farming, when practiced with regenerative techniques like cover cropping and crop rotation, greatly increases the richness and diversity of the soil microbiome. Within a healthy soil microbiome, soil microbes interact with the roots of plants, stimulating them to produce health-promoting and disease-fighting molecules—in particular the polyphenols. While plants grown conventionally with chemical fertilizers have higher yields, they are deprived of this prompt from soil microbes and need increasing amounts of chemical pesticides to fight diseases.

When it comes to meat, industrial production involves routinely giving low doses of antibiotics to livestock to stimulate their growth, regardless of whether they’re sick. This background antibiotic exposure not only changes the animals’ microbiota and increases the growth of antibiotic-resistant strains, but also suppresses the diversity and relative abundances of our own gut microbes. Switching to meat from organic, antibiotic-free animals minimizes this. Also, if animals are grass-fed, their meat has a beneficial higher ratio of omega-3 toomega-6 fatty acids.

Even a small reduction in our consumption of conventionally raised meat and dairy products could reduce greenhouse gas production and help prevent further declines in the diversity of plant and animal species around the world.

How to Handle Your Ingredients

Food preparation can destroy fiber and polyphenols, the nutrients our microbes crave. Here are several simple ways to preserve them.

First, don’t overcook your food. Heat can degrade complex fiber molecules into simple carbohydrates, which, like processed carbohydrates and sugars, are easily absorbable in the first portion of the small intestine, resulting in blood sugar and insulin spikes. This early absorption starves the microbes living further down the digestive tract and prevents them from converting fiber—their food—into short-chain fatty acids that benefit our health. Prolonged cooking also destroys polyphenols in fruits and vegetables.

For much the same reason, eat most fruits raw and vegetables raw or only briefly cooked, so their fiber and polyphenols make their way to your microbes intact. Dried beans and other legumes obviously require cooking, and retain their fibers.

Avoid juicing when you’re making a smoothie; use a blender or food processor instead. Juicing strips the fiber from fruits and vegetables and leaves only sugars—which, as we’ve seen, are rapidly absorbed, with adverse effects for us and our microbes. Blending up whole fruits and vegetables preserves their fibers, slowing the absorption of sugars and giving our gut microbes the food they need to thrive.

Lastly, keep polyphenol-rich foods airtight and away from heat and sunlight. Tightly seal your red wine (or pump the air out with a small, inexpensive wine vacuum pump); keep your tightly closed olive oil in a cool, dark cupboard or stainless steel container. Air, heat and UV light will degrade certain polyphenols.

Adjust Your Diet to Treat Disease

A flood of dietary recommendations now exists for a wide range of symptoms and disorders. Unfortunately, these recommendations are often driven more by business considerations than by rigorous scientific evidence. However, if you are suffering from a gastrointestinal disease such as celiac disease, true food allergies or irritable bowel syndrome, personalize the advice above, which may require medical supervision. These strategies are now well known: If you have celiac disease, strictly avoid gluten-containing foods. If you suffer from a serious allergy to shellfish, or peanuts, don’t touch them. If you are lactose intolerant, reduce or eliminate milk products. In the case of irritable bowel syndrome, start with the optimal microbe-nourishing diet. Then carefully identify the foods that consistently increase your symptoms of bloating and abdominal discomfort, and eliminate them. If you struggle with your weight and have been diagnosed with metabolic syndrome (increased body mass index, blood sugar and lipids, and elevated blood pressure), try a limited course of time-restricted eating (under medical supervision), and then switch to the optimal diet for long-term health.

The Path to Diversity, Inside and Outside Us

Diversity is a universal indicator of healthy ecosystems, both at the mi-croscopic and macroscopic level. Unnoticed by the public, the food industry and the healthcare system, the rapid industrialization of the world has come at a great cost: the progressive and accelerating decline in the diversity of all life-forms on planet Earth, including the mi-croorganisms living in the soil, the water and our gut. The only species that have moved against this trend are humans and farm animals, in particular cows and chickens, whose numbers have swelled as many wild species have declined.

There is a growing recognition that the degradations of all these ecosystems, including our gut microbiomes, are not occurring as independent phenomena but are closely interconnected. While some of the already vanished species in our gut and around us may be lost forever, there is hope that a radical change in our awareness of what and how we eat can help restore a more diverse world within and around us. Eating to feed our personal microbes can nourish the planet too.