UPDATE: On November 18th, 2022, Washington State Commissioner of Public Lands, Hillary Franz, announced that Cooke Aquaculture’s leases for net-pen fish farms in Puget Sound would not be renewed. This means Cooke’s net pens will be gone by the end of the year. Even better, the Commissioner banned net pens from state property forever. Huge congrats to our partners at Wild Fish Conservancy for leading the charge, to tribal nations, businesses, chefs, fishing groups and citizens for their advocacy, and to our Provisions customers who supported the effort through their purchases and by signing the original petition. And of course, a special thank you to Commissioner Franz for listening and making the decision for wild salmon, orcas and a healthier, more resilient Salish Sea. This is a victory we can all savor together.

On a humid, smoky September morning back in 2017, the kids and I loaded our little skiff for a stand-off a few miles south of our home on Bainbridge Island. Under a sky made eerily red by wildfires raging across Washington State, we packed the cardboard-and-marker signs we’d made, a bullhorn, the dog, and “just in case,” we stashed a couple of six-weight fly rods under the bow. Over the past weeks we’d hung notices on bulletin boards around town, posted to social media and e-mailed everyone we knew, but had no idea if anyone else would show up to the Wild Fish Conservancy protest of Cooke Aquaculture’s net-pen salmon farm. We also made room for a cameraman, along to shoot footage for the Patagonia film Artifishal, which focuses on the damage hatcheries and fish farms have on wild salmon populations. As a favor to us, and for the cause, our friend David had a full film crew aboard his boat as well. When we passed beneath the Agate Pass Bridge, I was already dreading the possibility of a small, or worse, nonexistent crowd.

“Our local southern resident killer whales are starving to death for lack of large wild Chinook salmon they need in their diet to survive.”

What we couldn’t know then was that this was only the beginning of a long and arduous battle, and that a true solution wouldn’t come to light for three more years.

Photo by Wild Fish Conservancy

Photo by Wild Fish Conservancy

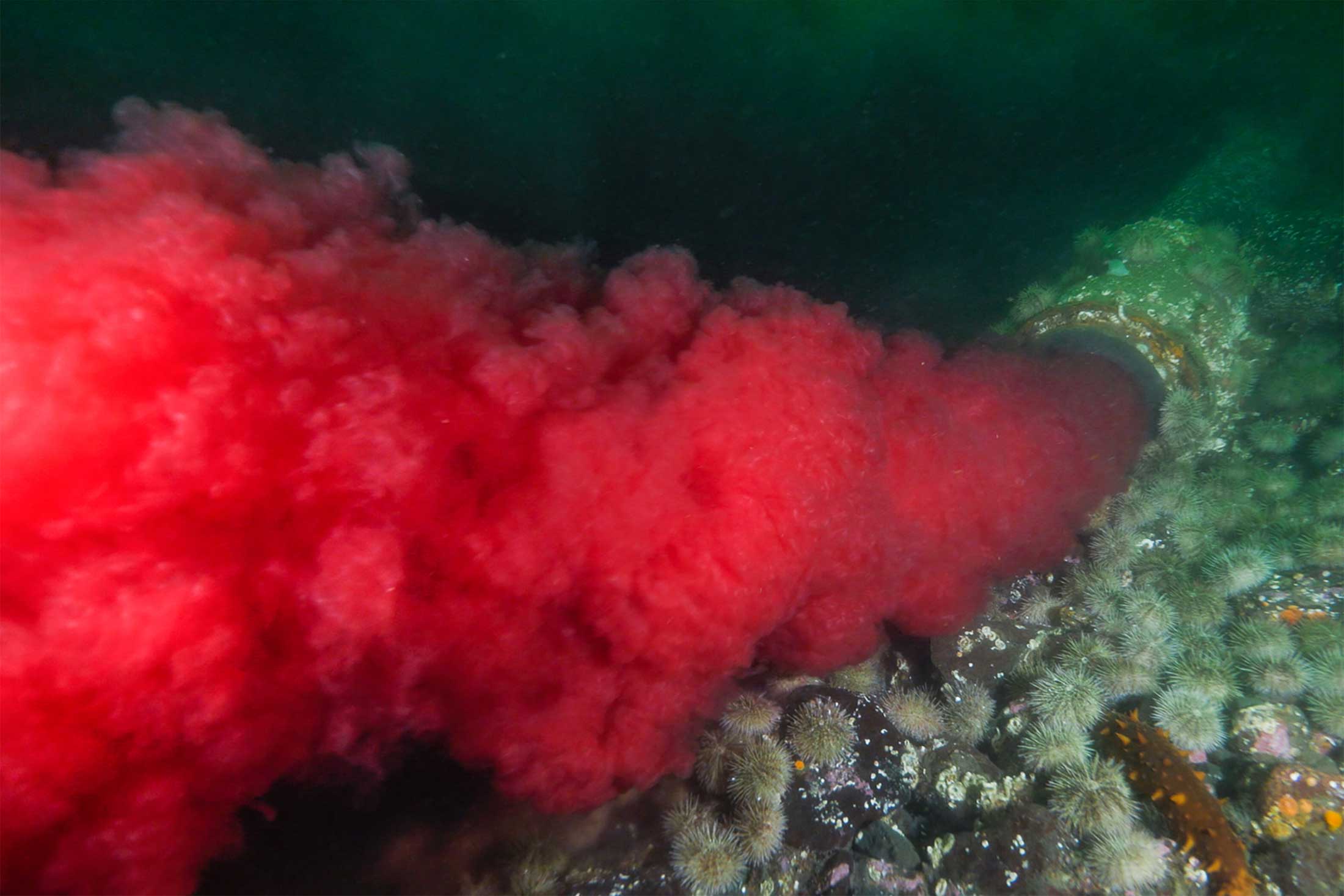

Only one month before, Cooke had made headlines around the world with the spectacular collapse of its net-pen salmon farm off Cypress Island, 70 miles north of Seattle. The collapse resulted in more than 260,000 non-native, domesticated Atlantic salmon escaping into Puget Sound. Later, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and Wild Fish Conservancy, in independent studies, found that 100 percent of escaped fish they tested carried piscine reovirus (PRV), a highly contagious, exotic virus that can infect and harm our native, wild salmon and steelhead. By winter, the escaped fish were found spread throughout the region’s bays and rivers for hundreds of miles.

As we made our turn into the calm waters of Rich Passage, we could smell the rotting-fish aroma of the net pens long before we could see the facility itself. Cooke’s Bainbridge net pens are anchored to a reef considered so valuable to the Puget Sound ecosystem that it was long ago set aside as a State Marine Protected Area, a particularly cruel irony the kids and I discussed as we approached. Then the boats came into view: Commercial netters, center consoles, tribal crabbers, sailboats, bowriders, paddleboards, skiffs like ours and more kayaks than we could count. On every vessel, people stood waving signs and honking horns. Game on. Skyla and Weston lifted their signs, shouted, waved and sounded the air horn we normally reserve for emergencies. It occurred to me, though, that this was an emergency.

Photo by Ben Moon

Photo by Ben Moon

It wasn’t just the one net-pen facility off the south end of our home island that we were protesting. It was all of Cooke Aquaculture’s net-pens scattered across the Salish Sea. It was the way Cooke officials lied to the public and regulators about the cause of the Cypress Island collapse (The eclipse? High tides? Really?) and underreported the number of escaped fish. It was how they fought the fines and other repercussions of their negligence. And it was Cooke’s dismal environmental record in Scotland, South America and Canada.

For the kids and me, though, the impacts of the net pens were plenty visible right here at home. The salmon we love have been on a long and precipitous decline, and the science shows open-water net pens, with their legacy of disease, parasites and pollution that pass freely into waters used by migrating wild salmon and steelhead, contribute mightily to the problem.

Today, the average size of an adult Puget Sound Chinook salmon has shrunk from 25 pounds to less than 10. Our local southern resident killer whales are starving to death for the lack of large wild Chinook salmon they need in their diet to survive. Wild steelhead populations hover below four percent of the historical average. All three species—Chinook, orcas and steelhead—are currently listed under the Endangered Species Act. Washington taxpayers and tribal nations spend tens of millions of dollars every year to recover them.

Photo by C. Emmons / NOAA Fisheries Taken under Federal Research Permit

Photo by C. Emmons / NOAA Fisheries Taken under Federal Research Permit

At the same time, we’ve allowed a multinational corporation, Cooke Aquaculture, to pollute our public waters with untreated fecal waste, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and the aforementioned parasites and disease, all of which are known to harm the three species listed above—and countless other forms of marine life—that we’re paying so much to protect. I’m not sure if that’s irony or just plain old-fashioned shooting yourself in the foot.

While Cooke executives make decisions from their offices in New Brunswick—decisions that affect marine life around the globe—the impact of their operations is left for locals to deal with. In the case of Puget Sound, it’s the citizens of Washington State and the tribal nations that call this region home. As my friend Willie Frank III, the 7th Council Member for the Nisqually Tribe, says, “If you care about salmon and all the communities and creatures that depend on them, as we have for thousands of years, the Cooke net pens need to go.”

A few months after the net-pen protests, the state legislature, reflecting the will of Washington citizens, voted to end Cooke’s tenure in Puget Sound with a landmark law, HB 2957, which effectively banned Atlantic salmon net-pen aquaculture from Washington’s marine waters by 2025. Skyla, Weston and I danced in celebration at the news, and the kids learned a valuable lesson: protest works.

Less than two years later, the kids learned another lesson: When it comes to corporate profits, it ain’t over ’til it’s over. There’s a loophole in the new law, and Cooke moved to exploit it. The law, as it was worded, referred specifically to non-native marine finfish net-pen aquaculture. Last year, Cooke announced it could avoid eviction by shifting their livestock from Atlantic salmon to a domesticated, farmed version of steelhead, which are native to the region. In addition to all the same problems inherent to open-water, net-pen feedlots, these “steelhead” are even more dangerous to the ecosystem than Atlantic salmon. When the inevitable escape happens—and given the dilapidated state of the Cooke net pens and their record, it is inevitable—the domestic steelhead have a much greater potential for interbreeding and degrading the fragile gene pool of endangered wild steelhead.

Photo by Tavish Campbell

Photo by Tavish Campbell

But, just as it’s true for corporate profits, the same determination applies to conservationists: It ain’t over ’til it’s over. Now there’s a bold new plan created by Wild Fish Conservancy, and supported by a broad coalition of tribal, commercial and recreational fishing stakeholders, food businesses, conservation groups and concerned citizens from across North America. “We’ve applied to the state to take over the leases where Cooke’s net pens are located,” says Wild Fish Conservancy executive director Kurt Beardslee. “If we’re successful, Cooke will not be invited to stay on as tenants.” Instead, the sites will be vacated and restored to their natural state for the common good of human and marine life.

So that’s the plan: Come together, lease the net-pen sites out from under Cooke, and evict them. That’s it.

On a personal level, it’s important for me to show Skyla and Weston that hard work and doing what’s right wins out in the end, and that activism does, in fact, work. From a larger perspective, though, it’s a decisive, powerful way to give wild salmon, steelhead and orcas a chance to thrive once again in the waters of the Salish Sea. All it takes to start is signing the petition, which will go to Washington State Commissioner of Public Lands Hilary Franz. Her office will award the leases, and it’s up to us to remind her that we don’t want salmon feedlots or their pollution in our waters. We can do this. Let’s take back Puget Sound. As 10-year-old Weston wrote on his protest sign back on that smoky day in 2017, NUCK THE FET PENS!

Photo by Eiko Jones

Photo by Eiko Jones