Wheat Sourcing

Photo by Amy Kumler

Wheat feeds millions of people around the world every day. How we farm this single plant can have a significant impact on the Earth and the life it supports. That’s why we’re committed to using wheat grown with regenerative organic practices that build topsoil and restore biodiversity. We also love the fresh taste of our Regenerative Organic Certified™ wheat flour, which we use to make our crunchy and flavorful crackers.

Nutrition + Flavor: Naturally Good

Our organic Edison wheat has a beautiful golden color and a buttery taste. To turn it into flour, our millers stone-grind the entire wheat berry, then carefully sift for a versatile all-purpose flour that retains the flavorful, nutritious germ and bran.

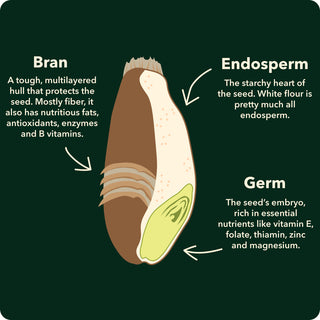

Most all-purpose flour comes from industrial roller mills that strip out the wheat’s bran (the hard “shell” of the wheat berry, which is rich in fiber) and germ (the inner sprouting section, full of minerals, B vitamins, antioxidants, phytochemicals and flavor). Roller-milling extends the shelf life of flour but empties it of nutrients, so mills “enrich” the flour by adding vitamins and minerals. Some mills also add bleach to the flour, for whiteness; potassium bromate (linked to cancer and banned in several countries), for rise and elasticity; and vital wheat gluten, also for elasticity, making bread even less digestible for people with gluten issues.

Our partners at Cairnspring Mills, in Washington State, add nothing. They simply follow the ancient tradition of grinding wheat berries between two stones, retaining every part of the berry and its complex nutrients. The result is a versatile, all-purpose flour that’s remarkably flavorful, naturally nutritious and refined enough to make our light, crisp crackers.

Sourcing: Washington Grown + Milled

Photo by Amy Kumler

All of our wheat comes from just two farms in Washington state. It’s milled in-state too, which benefits farmers and the local community.

Hedlin Farms, in the Skagit Valley town of La Conner, was founded more than 100 years ago. Dave Hedlin and his wife Serena Campbell run the farm now, raising nearly 100 varieties of fruits and vegetables, in addition to the wheat they produce for us. Andersen Organics is a father-daughter team in Othello, Washington. They’re best known for producing onions on the 600 acres of organic land they farm in Washington's Columbia River basin. But they grow wheat as a cover crop between their onion harvests, and it’s simply incredible.

Wheat from both farms goes to Cairnspring Mills for processing. The mill, 10 miles north of Hedlin Farms, does much more than buy and mill flour. Founder Kevin Morse, a former director at The Nature Conservancy and a big-picture guy, pays farmers a premium to grow specialty varieties that are disease-resistant, flavorful and great for baking. His goal: To help farms stay financially viable while championing flour as a local, fresh food. “Farmers have been in a race to the bottom with commodity markets,” says Morse. “We’re giving them an alternative so they can prosper outside of the industrial food system.”

Photo by Amy Kumler.

Enviro: Grown to Restore

Photo by Amy Kumler

Rather than synthetic fertilizers or pesticides, our farmers use regenerative practices to build the fertility and health of their fields.

Our wheat farmers add nutrients back to the soil with cow manure from neighboring dairy farms and till minimally, further protecting the microbiome of the soil. Crucially, they also plant cover crops between harvests which prevents erosion and builds up precious topsoil.

Instead of relying on toxic chemicals, our farmers rotate their crops so insects and diseases can’t become entrenched, and figure out specific, natural ways to eliminate pests. These practices help crops stay healthy, resilient, and able to outpace weeds, a major issue that, on conventional farms, gets resolved with herbicides.

Our farms are Regenerative Organic Certified™, a stringent standard that assesses the entire farm system—not only soil health but also animal welfare and the well-being of farmworkers.

Culture: Reviving a Heritage of Grain

A threshing crew in Washington state, 1903. At that time, wheat was a fresh crop, milled and sold locally. Photo: Ivy Close Images / Alamy

Wheat arrived in Washington State in the 1820s, brought by employees of the Hudson Bay Trading Company.

Wheat thrived in Washington, and by the early 1900s, roughly 160 local mills were grinding wheat from local farms. The transcontinental railroad and industrial agriculture changed that picture. Today, a few giant mills process most of the state’s wheat and then export it, mainly to Asia and the Middle East. Across America, it’s much the same story: Wheat, once a fresh crop with hundreds of local varieties, is now bred for sameness. Massive leaps in farm productivity, efficiency and yields do feed the world, but it comes at a cost.

Seeking the local flavors of the past, a determined group of farmers, millers, scientists and bakers are working to revive regional grain farming. At Washington State University’s Bread Lab, wheat breeder Stephen Jones and his team develop wheats adapted to western Washington’s cool, wet climate. Then they work with farmers, millers, bakers and distillers to integrate these new grains into the local food supply. Our mill, Cairnspring, got help from Breadlab as it was finding its footing. Now Cairnspring brings unique local wheats to market—like the delicious Edison variety we use for our crackers.